The Last Frontier: How Louis L'Amour's Son Is Fighting Publishing's 'Men Don't Read' Myth

The Truth About Men's Reading Habits and Why Traditional Publishers Are Missing a Massive Opportunity

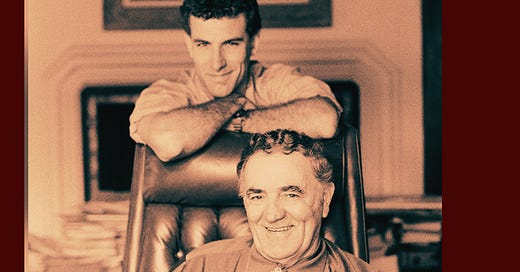

When my video about the absence of contemporary men's fiction went viral last month, I struck a nerve that resonated far beyond my usual audience. The comment section flooded with responses from men who felt invisible in today's publishing landscape—readers hungry for stories that spoke to their experiences (from their perspective) without apology. Among the avalanche of messages that landed in my inbox was one that stood out: an email from Beau L'Amour, son of legendary author Louis L'Amour and custodian of one of the most successful literary legacies in American history.

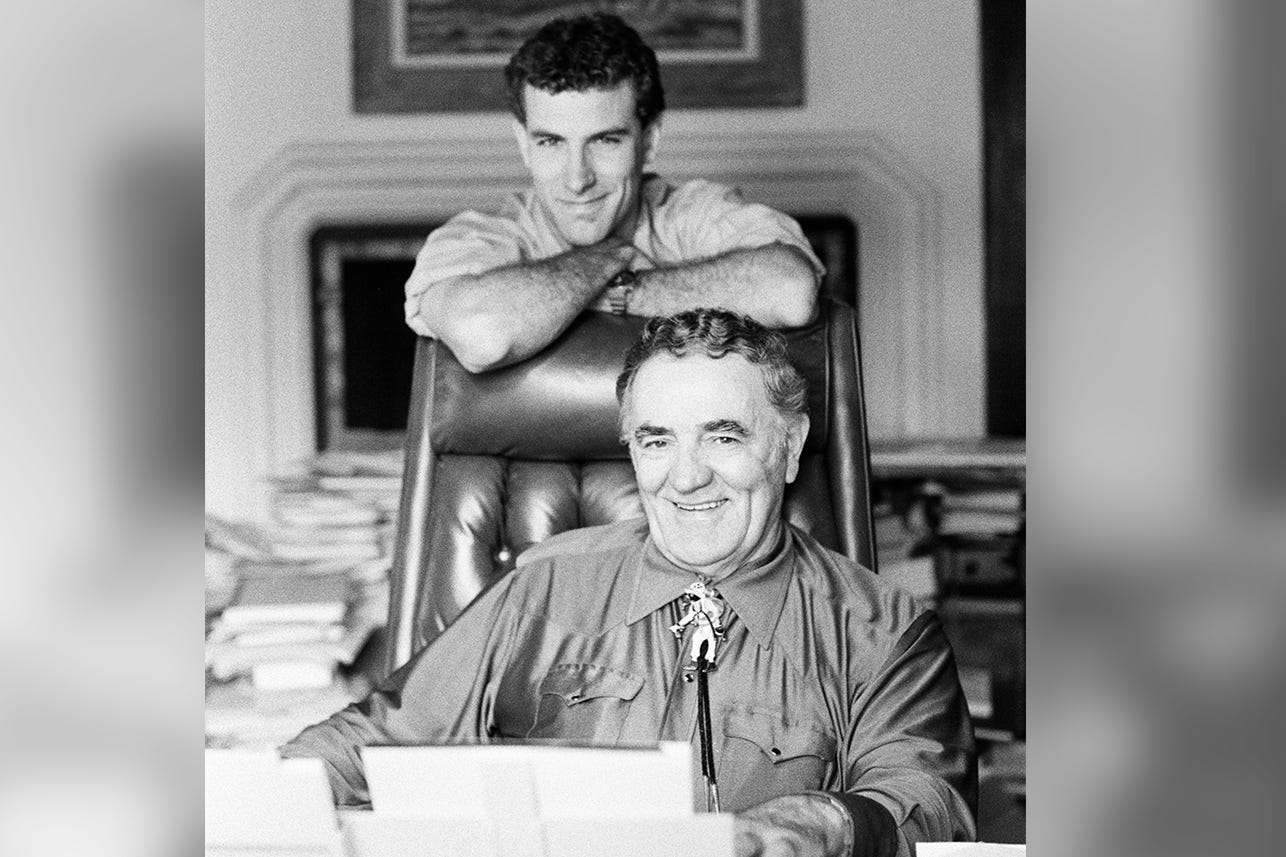

Louis L'Amour's novels have sold over 330 million copies worldwide, making him one of the most commercially successful authors of all time. His son Beau has spent decades not only maintaining this legacy but expanding it through audio productions, film adaptations, and careful curation of previously unpublished works. Yet he operates in an industry increasingly skeptical about fiction aimed at male readers.

"I can't tell you how many times in the last two decades I have been informed, 'men don't read,'" he wrote to me. "That's by people in publishing, people I work with. People who know my business is still selling male-oriented fiction and is, year on year, among the top 50 authors in the world."

The disconnect couldn't be more stark: while publishing executives declare the male reader extinct and focus on female-centric romantasy, L'Amour's frontier tales continue to sell millions of copies annually. Having worked in the business since the 1980s and grown up around it since the 1960s, Beau was kind enough to offer his view of how the industry has evolved—and what's been lost along the way.

In an era when publishing houses increasingly focus on female readers—who, admittedly, buy more books—Beau L'Amour stands as both a veteran of the “good ol’ days” and perhaps the most clear-eyed critic of the present. Our conversation touched on a lot of topics, all while circling back to a simple truth that the industry seems determined to forget: men do read, if you give them stories worth reading.

The Keeper of the Frontier: Beau L'Amour on His Father's Legacy and Publishing's Forgotten Male Readers

K: You’ve been in the the publishing business since the 1960s. What are the most significant changes you've witnessed in how publishers approach male-oriented fiction over those decades?

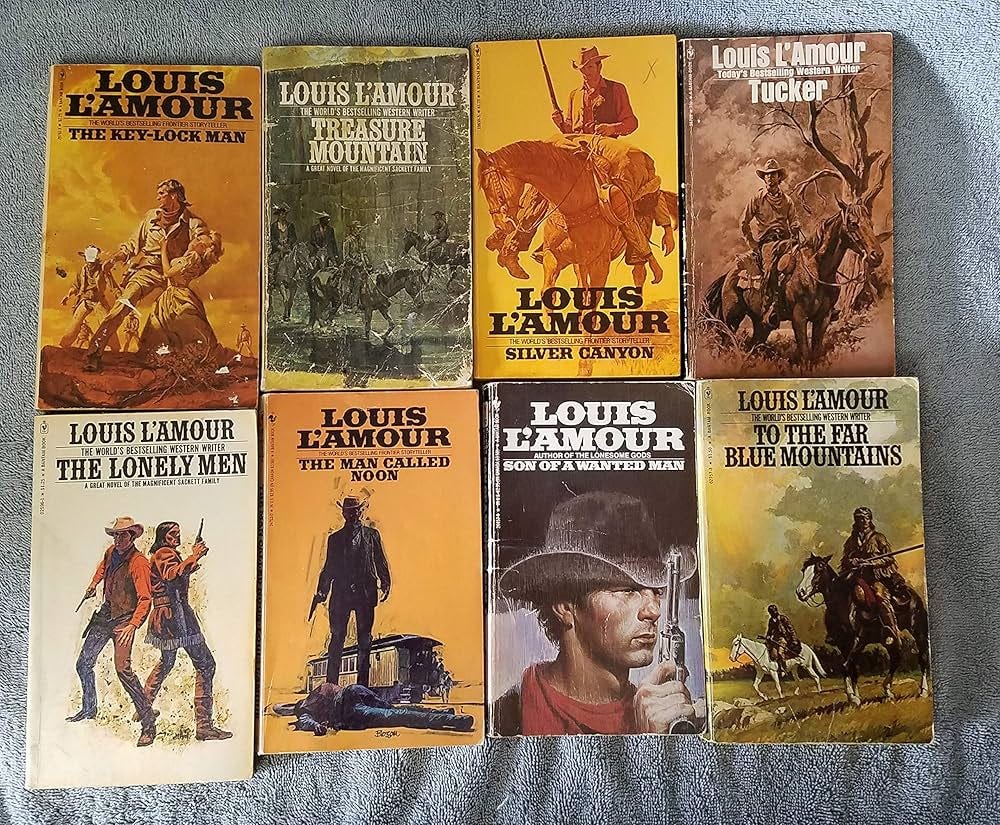

B: I think you need to start by looking at the pulp magazines of the pre WWII years. That’s the business the paperback industry grew out of and it’s also the origin point for many popular authors of the mid 20th century, the ones who inspired a lot of young men to love reading . The pulps divided up fiction genres into dozens of tightly targeted categories, to the point where you had things like “Ranch Romances,” which published vaguely female-oriented westerns, and “Sky Fighters,” which was all aviation focused adventure stories.

The landscape was filled with material aimed at boys and men, as well as women. There were hard boiled crime stories, which I consider different from ‘whodunit’ style mysteries, which are often more popular with the female audience. There was the high adventure genre (ala Raiders of the Lost Ark), science fiction, and westerns, all of which tended to be long on plot, often referencing hardware of some sort, and were kind of “outward facing,” and thus male oriented.

When the paperback book business started, after WWII, each publisher maintained racks of their own authors and various types of books intermixed. As the selection of books grew larger and paperbacks migrated more and more into bookstores and away from magazine stands, this became awkward and disorganized. By the late 1950s the booksellers were calling for what they, somewhat ironically, termed “integration.”

This meant all the publishers’ products would be mixed together, but there had to be some kind of organizing principle to help the customer discover the sort of thing they wanted to read. That’s where the modern, limited, and rigid, version of category or genre fiction was born.

The paperback business, in the early days, was mostly run by men. Sales departments still had guys who had grown up in the mob-controlled world of magazine distribution, where newsboys would knife each other to get the best corner. The editorial and executive suites were full of war veterans, at Bantam several had belonged to the OSS, sort of a WWII mixture of the CIA and the Green Berets.

They were, however, business men. They were not disconnected from the companies profits by many layers of management or the ownership of another, larger, corporation. They clearly recognized the sales potential of material aimed at women and they also stood behind female authors.

The benchmark for sales in my father’s era was Agatha Christie, with other authors like Barbra Cartland and Jackie Collins also racking up significant sales. There were even standouts in the more male oriented genres of hard boiled crime, Patricia Highsmith, and science fiction, Alice Mary “Andre” Norton. I’m just pulling all this from memory, I’m sure I’m missing many names and details.

It was generally accepted that male readers would head toward westerns, crime stories, and science fiction, while women would choose romance, whodunnits, fantasy, historical fiction and a sort of “contemporary social drama” that fell under the general fiction banner.

It was possible that women also read a bit more “classic literature” in those days but I’m not sure this is true. It’s an odd distinction because a good deal of it, think of Dumas and Dickens, was just well done popular fiction that had stood the test of time.

In my opinion, the type of material that was published improved but did not change all that much until the late 2000s … with two exceptions.

The Suicide of Westerns and Science Fiction

The mid to late 20th century western genre always had a narrow vision of its potential, focusing on the slice of history from 1865 to 1900 and only vaguely connected to the rest of the world. It degenerated, with the help of Hollywood, into a kind of kabuki theatre of diminishing possibilities. My father and others tried to expand its horizons but the shrinking number of fans, as much as they wanted new material, would accept little change. Soon he was one of the few who were left because he had learned how to gently push the edge of the envelope without breaking anything.

Science fiction died with Apollo. Once it was clear that getting anywhere from earth demanded technology that could barely be imagined, the genre slowly began to morph into more and more dystopian earthbound futures. Some of the best SF was written in this era but soon even masters like Larry Niven had slipped sideways into experiments in fantasy.

Cyber punk seemed to be the nail in the coffin. The future had just become a bleaker version of what our lives already were. For a while, Lou Aronica, founder of the Spectra imprint at Bantam/Dell fought a single handed battle against these cynical forces.

Those were two male oriented genres that went through hard times just before the larger changes that came around in the late 2000s.

The Demographic Turn of the Tide

The demographic balance of men and women in publishing and, just as important, where they came from and how they were educated, improved throughout the late 20th century. Recognize, I haven’t studied the metrics, these are just my recollections … very unscientific.

I had contact with only one company but due to continual consolidation this grew from Bantam Books through the acquisition of Doubleday, Dell, Delacourt, all the Random House companies and Penguin. People I worked with eventually worked at every major publisher in the country including Amazon.

Throughout the 1980s, when I started work, the number of women in all positions increased every year. Most notably this was in editorial, sales, new and ancillary markets (like audio publishing), and as lawyers. It’s only my perception, but I remember many of these ladies coming out of good schools in “middle America.” Publicity and marketing was already well staffed with women as were areas like accounting and subsidiary rights. Many of the new hires were very dynamic and were rapidly promoted.

Because of this, the late 1990s and early 2000s were a great time to be working in publishing. Markets expanded, inefficiencies shrank, the quality of the product and its packaging went through the roof. The spectrum of what was published was very broad.

From my experience – as a man – a good mixture of men and women tends to create a more polite workplace. Too many men and the atmosphere can get a bit rough and in-your-face … unfortunately the opposite end of the spectrum is also true, a female heavy workplace becomes bland, risk averse, and, while it’s just as competitive, the jockeying for power is much more behind the scenes and often interpersonal rather than over policy.

Men fall into hierarchies, if one guy can’t be the boss, he’ll make himself into the expert that supports the boss, and on down the line, a giant pyramid of teamwork. The women want cooperation through consensus, everyone on the same page and no one dominant. Both systems have their strengths and weaknesses but they are clearly strongest, over the long run, if they operate in a balance.

I saw two changes, one in product, the other in personnel, occur around 2010. Starting in the 1990s there was a myth going around the business that “fewer people read.” The remaining customers, so the story went, were very dedicated, so the goal was to sell them upscale, attractive, and somewhat more expensive books, to make up the difference. More hardcovers, at a higher price point, were pushed into the marketplace. This had the effect of edging genre fiction slowly out of the market and replacing it with general fiction or literature.

It’s worth noting that the book business will always shoot for the center of any demographic … because it’s easy and cheap. But that’s not where the biggest pay off is. If I try to sell a Louis L’Amour title to the people who have a whole library of Louis L’Amour books I might sell one or two, but if I find a fan who only has a couple, or a new reader, I can sell them a hundred. As an executive in any business it’s hard to justify the more difficult approach, but that’s where the money is.

Anyway, at that same time there was a great deal of consolidation and restructuring. The older men, often highly paid, were let go. Since the number of women employed in the business had increased they moved up. It didn’t hurt that they were probably younger and hadn’t hit the higher levels of executive pay yet either.

However, many of the new hires had grown up in an environment where most of those they dealt with were women. They didn’t have the opportunity of working in an at least 50% male office where they were constantly challenged by the viewpoints of men, and (male or female) long-term veterans of the business, the street fighters who could sell books out of the trunk of their car. Some of those people were still around (and still are) but many have been promoted so far up the ladder that they don’t really serve as the sort of mentors or examples that they used to.

Many of this new group also seemed to have a slightly different background. The middle American values of the ‘80s and ‘90s hires were slipping away. New York has always been insular but now the situation was beginning to damage the business. The size of the companies isolated them from the marketplace. An echo chamber was being constructed.

The “Men Don’t Read” Lie

Now the story became “men don’t read” … very similar to the myth that readership was dropping off. I am sure that both of these things are true to a certain extent and it was also true that there were ways that being female helped sell books. A lot of librarians were female, same with educators, same with the members of informal reading groups and clubs … remember that the business, most businesses, will take the easiest path, even if it’s deadly in the long term.

And … the nature of the culture changed too. Overnight the sort of progressives who found authors like James Ellroy and Chuck Palahniuk excitingly edgy and subversive vanished. Now politeness and safety were the watchwords.

I suspect that if an executive had to go to lunch with four of her contemporaries, she really couldn’t get away with bragging about how she’d just published a work of hard science fiction. The other ladies would look at her with frowns of incomprehension.

Genre fiction, the old male oriented genre fiction, is just so 20th century. Uncool. This sort of thing is an issue in Hollywood too, with things like westerns. The creative executives are willing to say they are making a Kevin Costner or Clint Eastwood movie … but they’ll never say the word western first.

Until very recently, publishers never thought of readers as their customers, the bookstores were their customers. One of the reasons it seems they have difficulty comprehending the market is because of this.

“Fewer people read.”

“Men don’t read.”

Both sound like a story told by the hardback publishers of the 1950s. “Americans don’t read.” When paperbacks appeared they thought they were a fad, a flash in the pan. They never thought to consider the magazine reading public, especially the pulp magazine reading public … those people weren’t real readers. Or something.

Before paperbacks there were fewer than 500 bookstores in the country with most of them being in the northeast. You brought out your literary novel and you might sell 5,000 copies, then make a subsidiary rights sale to a subscription book club. No one had to think too much. Expectations were uniform. Then came Ballentine, and Faucett, Gold Medal, Ace, and Dell. Sales were in the millions.

Americans did read, it just so happened that speculatively spending money on fiction made them price sensitive. It just so happened that having access to a rack in the supermarket or train station was easier than driving into the big city to find a book store.

Random House invented a sales and technology model very much like Amazon’s Kindle. They did not implement it because they were afraid to damage their relationship with the bookstores. Amazon’s size set off the huge wave of mergers, everyone trying to get big enough so they couldn’t be bullied by the biggest best bookseller in the market. Kindle wasn’t all that revolutionary … because publishers demanded the prices equal the physical books in the bookstores. Kindle Direct Publishing, however, was revolutionary. KDP writers can undersell the physical book publishers, the major publishers.

The fiction market is still price sensitive, just as it was 75 years ago. No one wants to risk too much hard-earned money on a novel that might stink. So far, KDP has no gatekeepers of either sex, saying things like “men don’t read.” Genre, sometimes as finely parsed as in the old pulp magazines, is helpful in searching out what you might want so it’s an important element to KDP’s marketing tools. And the last time I had a discussion with executives at Amazon they claimed that, by revenue, KDP (just the “directly” published titles not ebooks based on physical books) was earning more than all the physical books, audio books, and electronic books sold by the major publishers put together.

I suspect that while “fewer people read’ the problem is not as big as mainstream publishing makes it out to be. I wonder if “fewer men read” or if they have migrated to finding indies on KDP … I just don’t know. It is the place where men’s reading could most easily stage a renaissance.

Mainstream publishing is just out of touch and, since they all moved home during covid, it’s gotten worse!

K: Were there any promising authors, editors, publishers, or marketers you saw driven out of the publishing business by the increasing female domination of the industry?

B: No. Sort of. Not exactly. I’ve never seen anything like that, but in time of consolidation, older staff people were often replaced by younger, less expensive, workers and the younger generation is female. That said, I have heard women in the business say things like, “We won’t hire anyone who can’t multitask.” That means something, it’s not necessarily gendered, but it does mean something.

There is a pride in the business about being women publishing things for women. That’s nice and as it should be … but not at the cost of neglecting men.

K: You noted that your business is "still selling male-oriented fiction and is, year on year, among the top 50 authors in the world" despite being told repeatedly that "men don't read." Is there any response from the traditional publishing houses regarding this clear disconnect between industry perceptions and your sales reality?

B: Nope. I think they think we’re special, and to a certain extent, we are. Dad’s books are handed down from generation to generation. They could learn a lot about what they might do from our history but it’s also true that publishers publish, they don’t write. They can only discover a writer, they can’t create one.

They might ask us occasionally what we think is going on, even just as observers of the business. My mother has been around publishing since 1956. No one ever asks her anything. They think there is nothing to be learned from the past because the business is so different.

It is different. A little different. But it’s hard to tell from the top of a pile of 10,000 employees.

K: How has the management of your father's literary estate evolved to maintain relevance in a publishing landscape that seems increasingly uninterested in male readership?

B: I wish I had a good answer. Dad’s work, while unappreciated by critics, has a certain undying appeal. It’s the energetic way he wrote as much as the genre.

I do my best to put constant pressure on the marketplace and the publisher. When we discovered in the early 2000 that Random House (Bantam) was agonizing over wanting to raise prices even though they still had warehouses full of books, I arranged to give over a million copies to the various branches of the US military. The publisher got a write-off and we got to send samples to a captive audience of young people, some of whom might be converted into long term customers.

I produced a magazine of new western fiction for a while, The Louis L’Amour Western Magazine. We have a whole line of audiobooks that are produced like radio drama, I syndicated that to over 200 radio stations back in the 1990s. You have to keep your ear to the ground and be alert to opportunities.

We were very early to use Facebook’s targeted marketing tools (back when FB let you do this), much earlier than the marketing department at Bantam. There could be more opportunities like this, say, doing our own podcast, but that’s much more expensive and time consuming so I haven’t tried yet. I’ve tried a lot of stuff that failed. You have to keep messing around.

K: What systemic changes-within publishers, agents, or marketing-do you think are needed to prioritize and elevate fiction that appeals to masculine energy and male readers of all ages?

B: You have to get boys. My sister says that if you don’t get a boy between 10 and 13, you don’t get them at all. Unfortunately the marketplace for this age kid is fractured and each segment kind of turns into a silo. Each age range is sort of an island to itself with not much overlap.

I really started reading compulsively with Lester Dent’s amazing (though today probably dated) Doc Savage series. This was considered adventure fiction for a general audience, adults and kids, in the 1930s. I read the Bantam reprints in the 1960s and 70s.

If you crossed a down-to-earth “superhero” like Ironman’s Tony Stark and injected him into the mystery, political thriller and science fiction genres, that’s pretty much who Clark Savage Jr. was. It was very male oriented, with lots of action, exploration and gadgets (Dent, along with writing hundreds of short stories and magazine novels invented telephone answering machines, garage door openers and mine detectors for the US navy). I also devoured Edgar Rice Burroughs, Robert Heinlein, and later Larry Niven. A lot of kids of my generation read Ray Bradbury, a real poet. He might be kind of underappreciated these days … certainly he was under appreciated by us when we were youngsters.

All of this was hard hitting, fast moving, and relatively short fiction. Great stuff! Today the material for kids and young people is too careful … or too transgressive! It’s too inward looking, too slow paced, and not technical enough to really activate a boy.

Boys need to search maps, wonder how the gravity well of a neutron star could solve a murder, and imagine how the track of an outlaw decays after days of exposure to the weather. Boys need to read edgy, funny, dangerous feeling material.

I have no confidence that people in publishing will chase any of these values. It’s up to writers. With the demise of the book cover, the sales tools are going to be more multimedia, more expensive and more time consuming. It’s probably not going to be easy!

K: In an industry that increasingly focuses on trend-driven fiction, how can writers stay true to timeless storytelling values while remaining relevant?

B: I’m going to argue that it’s possible to create your own space within the trend. I hope that’s true. In his magazine writing days, my father wrote in many genres: crime, sports, high adventure, personal adventure (sort of like Hemmingway), historical fiction, westerns. When the pulp magazines died out, he nearly starved to death.

He recreated himself with western paperback originals. And then, after 6 or 8 years of success, he tried to branch out … and failed. Retreating back into the western genre, he solidly established himself, and then started to slowly and carefully stretch what was possible in a western, from the early frontier to science fiction. It took decades. It was a big, subtly executed, plan, but it worked.

Attack from within! Be subversive!

K: What marketing approaches have proven most effective for reaching male readers, and how do these differ from what mainstream publishers currently emphasize?

B: The military strategy, mentioned above, was great! I’m no expert but I’d recommend leveraging YouTube. The most innovative and risky would be to just get up and say this is for boys … boys who like to get dirty, break things, who have a lot of energy, who want to explore…

I’m just going to include a lengthy Robert Heinlein quote from his novel Glory Road which is a send up of the fantasy genre and also a commentary, if you read all the way through to the end, on sexual stereotypes. It may not be for conservative 10 year olds, however.

“What did I want?

I wanted a Roc's egg. … I wanted raw red gold in nuggets the size of your fist and feed that lousy claim jumper to the huskies! I wanted to get up feeling brisk and go out and break some lances … I wanted to stand up to the Baron and dare him to touch my wench! I wanted to hear the purple water chuckling against the skin of the Nancy Lee in the cool of the morning watch and not another sound, nor any movement save the slow tilting of the wings of the albatross that had been pacing us the last thousand miles.

I wanted the hurtling moons of Barsoom. I wanted Storisende and Poictesme, and Holmes shaking me awake to tell me, "The game's afoot!" I wanted to float down the Mississippi on a raft and elude a mob in company with the Duke of Bilgewater and the Lost Dauphin.

I wanted Prestor John, and Excalibur held by a moon-white arm out of a silent lake. I wanted to sail with Ulysses and with Tros of Samothrace and eat the lotus in a land that seemed always afternoon. I wanted the feeling of romance and the sense of wonder I had known as a kid. I wanted the world to be what they had promised me it was going to be--instead of the tawdry, lousy, fouled-up mess it is.”

No one has ever said it better.

K: Was there a book that your father wrote that he was disappointed in? If so, why? Also - the Broken Gun and Last of the Breed were 'modern' stories; was there a different strategy in writing or marketing those than his more traditional work?

B: LOL! He tended to be unhappy with them as he finished, feeling he could have done better. All but The Daybreakers, he knew he had hit gold with that one.

The Broken Gun and Last of the Breed were either end of the trajectory I mentioned above where Dad spent a couple of decades morphing his readers and the genre to his will. The Broken Gun is a (partially) contemporary western mystery published in 1966. Last of the Breed was published in 1986 and is a cold war thriller, with a Native American protagonist. If he had to write westerns to feed his family, he was going to figure out a way to expand the genre so that he didn’t get bored with it.

K: You compared current attitudes toward male readership to historical resistance to paperbacks. Do you see any parallels with emerging digital formats, and how might these create new opportunities for male-oriented fiction?

What advice would you give to contemporary authors who want to write for male audiences but face resistance from traditional publishing?

B: Men need you. Boys need you. I fear a future where the imaginations of our young have been robbed of the practice they are given with fiction, with decoding the alphabet into amazing stories and entertaining and educational experiences that we no longer can invent … not just stories but clocks, microwave ovens, and innovative software.

KDP, reading your own book on YouTube, various new mediums are open to you. Every time there is a monopoly, and the attitude in traditional publishing is that even though it isn’t quite the mega corp that Amazon is, some new system grows up in its shadow. Soon something will grow up to subvert Amazon. I’m stuck in traditional publishing, I’m not the best one to ask, but I’d say “Stay alert!”

K: What are your thoughts on the state of cover art in the modern publishing industry?

B: Groan! I love cover art. I’ve worked with some of the best art directors and illustrators in the business. In fact, there's a whole show of my Louis L’Amour covers going up in Trinidad, Colorado, in June!

But, with online sales, the whole concept is changing, and it’s going to keep changing. For the moment, it’s still considered important enough so that Amazon has its own art directors but real estate on your screen is at a premium, so I suspect it’s going to evolve.

I could go on and on about how to design a book cover but all that knowledge is specific to the old school book store business, so it’s probably obsolete.

K: Do you think the concentration of publishing into only a handful of major publishing houses has contributed to the decline in male readership?

B: It sure has … if only because lack of corporate diversity just leads to a lack of viewpoint diversity. If there was a male-oriented specialist publisher the way Tor specialized in Science Fiction, we’d all be better off. The consolidation of the business has made certain publishers very powerful. There’s an upside to that, but in shielding them from market forces it not only protects … it keeps them from learning. I guess the best position would be a company that was just vulnerable enough to be alert and energetic.

I have definitely felt there were moments where one publisher or another that I worked with would hesitate to make a move. I suspected that their thinking was, “If I do such and such, the repercussions will echo through the entire industry, so I have to be careful.”

That’s getting so big and influential that you become scared of your own (long) shadow! It’s probably not a good or businesslike attitude, but it was more fun when they were all just gutsy medium-sized companies who knew how to go for it!

K: Indie authors like Devon Eriksen and Matt Dinimann have carved out a space for male readers and are steadily gaining traction (in scifi and fantasy, respectively). Are there any current authors or publishers who you believe are successfully carrying on with your father’s legacy (either in genre, theme, or audience)?

B: Not my father’s legacy but his own: Taylor Sheridan, the screenwriter and director of Yellowstone and a bunch of great features, wins the prize for robust storytelling and the energy and pace of his creation, that’s for sure!

K: Looking ahead, what changes do you hope to see in publishing's approach to male readership over the next decade?

B: The last time I had in-depth meetings with our publisher was before the pandemic. Almost everyone seems to have moved home and the business is fractured; communication is very difficult. I do think it is possible to organize a business to run this way, but if they have bothered to do that it hasn’t become obvious to me. So, I see very little change, either because I’m cut off from it or because there isn’t any.

However, the possibility of more mergers may have been forestalled by the blocking of the Random House/Simon and Schuster deal. Maybe now everyone will have to get back to actually selling books rather than growing by colonizing other companies and being constantly distracted by the tumult of consolidation.

I fear there are too few who really remember how to sell books or are capable of reimagining how to do it for the coming age. Someone is going to learn how to do that … and they are going to win big!

BTW: There is a gigantic and very expensive book called The Trial that documents the PRH/SS non merger. It is a CIA level primer on the inner workings of big publishing.

K: Lastly, I got a lot of questions as to whether The Walking Drum would be finished by another author based on your dad’s notes and drafts. Any thoughts on that, or will it remain as he left it?

B: Several years ago I created a series of new books and new editions of old books called “Louis L’Amour’s Lost Treasures.” Two of the new books are titled Louis L’Amour’s Lost Treasures Volumes 1 & 2, and they contain dozens of previously unpublished stories, both finished and unfinished. Along with them, I have written as much of the story of how they came to be written as I can discover using notes, correspondence, interviews, and my own memories. I try to tell how they might have concluded, how they fit into Dad’s career.

I have also done the same with some 30 + of his well known novels, adding in a Lost Treasures Postscript to tell the story behind the story. Taken as a whole, it is kind of a professional biography or an in-depth look at the way the publishing business worked creatively, editorially, and promotionally, in the 20th century.

The third “new” book is No Traveller Returns, my father’s first novel. It was left behind as just a pile of somewhat interconnected chapters when Dad went off to fight in WWII and was never finished. I’ve done my best to recreate its style and turn it into the cohesive whole that originally wanted it to be.

There is another Lost Treasures project, which I wont say too much about at this time, that I am just about to finish. Given the typical time lines in publishing it will probably take over a year to get to market.

Will there ever be a sequel to The Walking Drum? I don’t know. Maybe.

But if you were to get ahold of the Lost Treasures edition, you will find an in-depth look at the story behind the writing of it and the lengthy time it took to get it published. The book was written around 1960 yet not published until 1984 or so. Part of Dad’s struggle to break away from only writing westerns.

Also included is a comprehensive outline for a sequel made up from a number of sources that was able to cobble together. So even if fans are not able to read the sequel itself, they can get a pretty good idea of what it might have been like.

Beau's passion for storytelling and for publishing men’s stories remains undiminished and should serve as an example to us all.

"Reading trains the imagination," he reminds me, "trains it for life, and for greater flights of fantasy, from envisioning a better civilization to the mechanics of a watch or rocket."

In a publishing landscape dominated by algorithms, there's something profoundly hopeful about L'Amour's enduring appeal. Perhaps the frontier isn't closed after all, but merely waiting for a new generation of storytellers brave enough to venture into territories the industry has declared abandoned.

For the indie authors who make up my audience, Beau's message rings clear: the readers are out there—millions of them—waiting for stories that move, that breathe, that don't apologize for speaking to the male experience. They always have been.

Write your books. And make sure those readers know about them. Simple as.

![The Walking Drum [Book] The Walking Drum [Book]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fcd21324e-7ce5-4b8c-b9b5-8dcdde77380b_1025x1200.jpeg)

This read hit me hard. I compare the sheer variety of books I had to read growing up in the 70s with what I see on the shelves today. I had all the 50s, 60s, and what was being written then - a treasure trove for boys.

Reading and looking through the equivalent spaces today the covers and writing seems bland and generic, aimed at the least common denominator and don't inspire in the same way. Combined with the franchise dynasties of movies and lack of unsupervised time, I often think something has been lost.

I write books for reluctant readers, or what the industry says is Boy, because you know “boys don’t read.” I started writing books for the 9-13 year old boy because while I love comic books, and graphic novels, that’s all my kids would bring home from the library. That was all there was. I wanted a book that was fun, and an adventure for them. So I went and wrote and as a result: I was rejected by 10 publishers all telling me the same thing, there isn’t a profitable market. Four books, two awards, and over 10k in sales (which is still small, but better than most indies), I can say there is a market, a very hungry market.